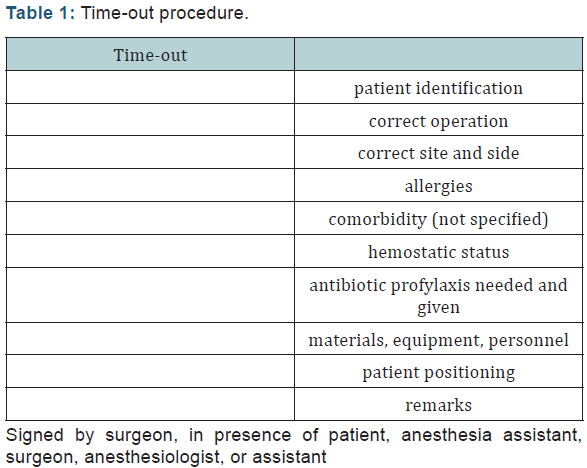

Since March 2010 the MoH stipulated that implementation of their SSC would be one of the core measurements for assessing hospital performance. These differences are highlighted in Table 1. Finally, there are several additional interventions found mainly in ‘ sign-in’ and ‘ sign-out’ components. Some single items in the WHO SSC which include multiple checks have been split (for example ‘ has the patient confirmed his/her identity, site, the procedure and consent?’ becomes four separate items in the MoH SSC). Although some deleted items are included as part of other formal checklists (for example ‘difficult airway and aspiration risk’ is part of a separate pre-operative anaesthetic check-list), these do not mandate that problems should be discussed with other team-members. However, five items found in the WHO SSC are removed completely. The three components of the SSC, colloquially known as ‘ Sign–In’, ‘ Time-Out’ and ‘ Sign-Out’ all remain as key checklist components in the MoH SSC. Although most element of the WHO SSC remain part of the officially designated MoH SSC there are sufficient differences to warrant comment. As a member of the World Alliance for Patient Safety, the Chinese Ministry of Health (MoH) has devoted long-term administrative efforts to implement the SSC albeit after significant modification, for example by increasing number of items from 22 to 33. Additions and modifications to fit local practice are encouraged’. In the WHO Guidelines for Safe Surgery 2009, it is written ‘ This checklist is not intended to be comprehensive. The WHO SSC has become one of the most significant and widely used innovations in surgical safety of the past 20 years. Other benefits which have been reported following implementation of the checklist include cost savings. Use of the WHO surgical safety checklist (SSC) is associated with a significant decrease in postoperative complication (30%) and mortality rates, improved compliance with standard processes of care and better quality of teamwork in the operating room. In June 2008 the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist (SSC) was published to help operating room staff improve teamwork and ensure the consistent use of safety processes. The World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Safe Surgery Saves Life campaign in January 2007 with the aim of improving consistency in surgical care and adherence to safety practices. Standardised audits are required to monitor and ensure checklist compliance. Cultural changes in nursing assertiveness and surgeon-led teamwork and checklist ownership are the key elements for improving compliance. The WHO SSC remains a powerful tool for surgical patient safety in China. One site had near 100% compliance in association with a circulating inspection team which had power of sanction. WHO SSC interventions which are omitted from the MoH SSC continued to be discussed over half the time.

Compliance in surgeon-dependent items of the ‘ time-out’ component reduced when it was nurse-led ( p < 0.0001). There was widespread acceptance of the checklist and its value in improving patient safety.Ĩ60 operations were observed for SSC compliance.

ResultsĪ total of 846 operating room staff and surgeons from 138 hospitals representing every mainland province responded to the survey. Adverse events which delayed the operation were recorded as well as the individuals leading or participating in the three SSC components.

Local data collectors were trained to document specific item performance.

We also conducted a prospective cross-sectional study at five level 3 hospitals. MethodsĪ questionnaire was designed to gain authentic views on the WHO SSC. Ten years after the introduction of the Chinese Ministry of Health (MoH) version of Surgical Safety Checklist (SSC) we wished to assess the ongoing influence of the World Health Organisation (WHO) SSC by observing all three checklist components during elective surgical procedures in China, as well as survey operating room staff and surgeons more widely about the WHO SSC.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)